Auf dem Platz vor dem Prager Hradschin sprach Barack Obama am Wochenende vor mehreren Zehntausend Tschechen, die dem amerikanischen Präsidenten einen herzlichen Empfang bereiteten.

Während der Platz, auf dem Obama sprach, von den Fahnen der Gäste aus ganz Europa und den USA gesäumt war, zeigte sich der tschechische Präsident, EU-Kritiker und Klimawandel-Leugner Vaclav Klaus von der brüsken Seite und ließ am Hradschin keine Flagge der EU aufziehen. Das tat der Stimmung jedoch keinen Abbruch.

Obama ehrte zu Beginn seiner Rede den in Tschechien hoch verehrten Staatsgründer Thomas Garrigue Masaryk:

Behind me is a statue of a hero of the Czech people – Tomas Masaryk.

In 1918, after America had pledged [zugesichert] its support for Czech independence, Masaryk spoke to a crowd in Chicago that was estimated to be over 100,000.

I don’t think I can match Masaryk’s record, but I’m honored to follow his footsteps from Chicago to Prague.

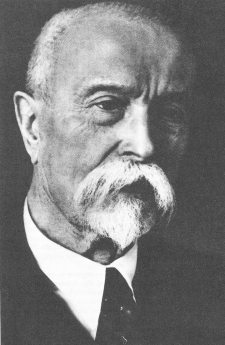

T.G. Masaryk, aus einfachen Verhältnissen stammend, habilitierter Philosoph, Schriftsteller, Professor, Politiker, 17 Jahre lang Präsident der Tschechoslowakei von 1918 bis 1935, vielbereist und mehrsprachig, war, so darf man ohne Übertreibung sagen, einer der herausragenden Staatsmänner Europas.

Schon zu Lebzeiten (1850 – 1937) genoß der zurückhaltende, vielseitig gebildete Mann enormen Ruhm.

Thomas Mann sagte über ihn und seine politischen Fähigkeiten: “Möge seinesgleichen, in welcher individuellen und nationalen Erscheinung nun immer, wieder auf Erden weilen, wenn eine europäische Konföderation nach ihrem gemeinsamen Oberhaupt Ausblick hält.”

Masaryk war mit der Amerikanerin Charlotte Garrigue verheiratet und hatte auch dadurch gute Kontakte in die Vereinigten Staaten. Über eine seiner Reisen berichtete Masaryk folgendes [Anm. TAB in Klammern]:

“Nach Amerika, nach Vancouver fuhr ich von Japan mit dem »Empress of Asia«. In Amerika warteten schon überall unsere Landsleute und amerikanische Journalisten auf mich, ich mußte mich an die amerikanische Publizistik gewöhnen.

Einerseits lebte ganz Amerika im [Ersten Welt-] Krieg in einer fieberhaften Erregung, alles war neu, es fühlte eine neue Beziehung zu Europa und zur Welt überhaupt; andererseits wirkte schon die Popularität unserer [tschechischen] Legionen, die sich damals schon mit der Waffe durch Rußland und Sibirien durchschlugen. Ich kannte unsere Soldaten und wußte, daß sie es schaffen würden. Die Amerikaner haben eine ungewöhnliche Bewunderung für alles Heldentum, und so machte der Zug unserer Fünfzigtausend durch einen ganzen Erdteil einen großen Eindruck auf sie.

Es war das viertemal, daß ich nach Amerika kam. Das erstemal war es im Jahre 1878, als ich Miß Garrigue [seine spätere Ehefrau, deren Nachnamen er als Mittelnamen annahm] nachreiste, und zweimal waren es Vortragsreisen, in den Jahren 1902 und 1907.

So hatte ich Amerika schon seit seinen Pionierzeiten wachsen gesehen. Ja, es gefällt mir. Nicht, daß ich die Landschaft liebte; die unsere ist schöner. Die amerikanische Landschaft ist wie das amerikanische Obst. Mir kam es immer vor, als schmecke das Obst dort irgendwie roher als das unsere, unseres ist süßer und reifer. Ich glaube, das macht die tausendjährige Arbeit, die bei uns in allem steckt. Und ebenso ist die amerikanische Landschaft irgendwie roher als die unsere. Für den Farmer, der mit Maschinen ausgerüstet ist, ist der Boden dort eine Fabrik und nicht ein Gegenstand der Liebe wie bei uns heute.

In Amerika gefällt mir die Offenheit der Menschen.

Selbstverständlich gibt es auch dort gute und schlechte Menschen wie bei uns; aber sie sind auch im Bösen offener.

So ein amerikanischer Wikinger ist völlig rücksichtslos und unbarmherzig; er ist ein offener Pirat ohne alles Getue und verbirgt sich nicht hinter einem moralischen oder patriotischen Paravent.

Die Guten wiederum gehen ebenso energisch dem nach, was sie für gut halten, sei es die Humanität, die Religion oder kulturelle Dinge. Sie sind unternehmender als bei uns. Da steckt immer noch viel unternehmungslustiges Pioniertum.

Die amerikanische Industrialisierung und das Arbeitstempo überraschen mich nicht. Da die Amerikaner mehr als 100 Millionen Menschen mit Ware zu versorgen haben, mußten sie sich daran gewöhnen, im Großen zu arbeiten; das bewirken die großen Ausmaße.

Auch in ihrem Kapitalismus sehe ich keinen Unterschied; so ein amerikanischer Milliardär ist wie ein Millionär bei uns, nur in größerem Maßstab. Man sagt auch: die Jagd nach dem Dollar!

Als ob es bei uns besser wäre! Der Unterschied liegt allerdings darin, daß wir in Europa eher dem Kreuzer nachjagen als dem Dollar und das so erniedrigend tun, als ginge es um ein Trinkgeld. Europa ist in dieser Beziehung weniger rücksichtslos, jedoch schmutziger.

Der Amerikanismus der Maschinen!

Maschinen haben ihre guten und bösen Seiten, ebenso wie der Taylorismus, die Rationalisierung.

Ersetzen die Maschinen die grobe, aufreibende Arbeit des Menschen, so ist es gut, man sollte mehr daran denken als an den Geldgewinn.

Mir war das amerikanische Arbeitstempo fremd; ich brauche zu jeder Arbeit sozusagen einen freien Rand, um sie mir in Ruhe zu überlegen. Unser Arbeiter ist vielleicht weniger flink, arbeitet aber gut und genau; die Qualität geht bei uns über die Quantität.

In Amerika wird die physische Arbeit höher geschätzt als bei uns; der amerikanische Student verrichtet in den Ferien Erntearbeit oder läßt sich als Kellner anstellen; bei uns wird die Schulbildung und besonders die akademische Bildung fast überschätzt. Der amerikanische Arbeiter ist im Vergleich zu unserm freier und hat seinen elbow-room; ist er geschickt, so hat er seinen Fordwagen und seinen Bungalow –daher gibt es dort keinen Sozialismus in unserem Sinne.

Schadet nichts, daß der sogenannte Amerikanismus zu uns vordringt. So viele Jahrhunderte haben wir Amerika europäisiert, jetzt hat es das gleiche Recht bei uns.

Wir amerikanisieren uns, aber vergessen Sie nicht, daß Amerika sich wieder je weiter desto mehr europäisiert.

Ich habe gelesen, daß jetzt zwei Millionen Amerikaner jährlich nach Europa kommen. Bedeutet Europa für ihr Leben etwas Gutes, so mögen sie es nur mit sich hinübertragen. Wenn man die neueren amerikanischen Autoren liest, so sieht man, wie streng sie die Fehler und Flachheiten des amerikanischen Lebens beurteilen.

Wären doch unsere Autoren so offen gegen unsere Fehler!

Die Zukunft liegt darin, daß Europa sich Amerika angleicht und Amerika Europa.

Kurz: mir bot Amerika vieles zu Beobachtung und Studium; ich lernte dort viel, viel Wertvolles.”

Über das Präsidentenamt – Obama könnte bei Masaryk gelernt haben

Masaryk schrieb, er habe im Jahr 1918 einigermaßen unvorbereitet und mit gemischten Gefühlen das Amt des Präsidenten übernommen. Über das Präsidentenamt schrieb er – und hier tauchen erstaunliche Parallelen zum Ansatz Barack Obamas auf – unter anderem:

“Ebenso wichtig wie die innere Politik war und ist mir immer die auswärtige, besonders in der Nachkriegszeit.

Hier muß man doppelt scharf voraussehen und auf die künftigen Dinge vorbereitet sein, niemals und durch nichts sich überraschen lassen.

Die Fragen, die in die Zukunft hinausreichen, sind niemals eng begrenzt; wir können nur dann Schätzungen nach vorwärts wagen, wenn wir im Rahmen des Möglichen den weitesten Zusammenhang und das Zusammenspiel aller Kräfte und Faktoren berücksichtigt haben.

Man muß wissen, um voraussehen zu können, wie [Auguste] Comte sagt. Die Außenpolitik ist und soll eine Sache der großen und konsequenten Staats- und Weltkonzeption sein.

Dabei stellt sich selten jemand vor, wieviel Kleinarbeit und unsichtbare Initiative die Außenpolitik erfordert. Für mich wenigstens ist sie eine unaufhörliche Arbeit. Ich habe mich während des Krieges davon überzeugt, welchen praktischen Wert in der Politik, namentlich in der internationalen, persönliche Beziehungen und ehrliche persönliche Informationen haben.

Sympathie und Vertrauen sind ein besseres Argument als Schlaumeierei.

Auf diesem Gebiet ist die Funktion des Präsidenten natürlich manchmal eine formell amtliche, aber unverhältnismäßig viel öfter eine private. Allerdings bin ich mirwohl bewußt, daß der Begriff des Privaten in diesem Falle durch die Gesetze nicht definiert ist. Und gerade bei uns ist es, weil unsere Leute früher wenig Verbindung zum Ausland hatten, noch immer nötig, informative und freundschaftliche Beziehungen zu unzähligen Menschen anzuknüpfen, die aus Interesse für unsern Staat und unsere Einrichtungen zu uns kommen. Nur die wenigsten wissen, wieviel Zeit ich dieser Arbeit gewidmet habe.

Viele Menschen besuchen mich nicht als Präsidenten, sondern als den Autor politischer und anderer Schriften, als den Urheber von Ideen, für die sie sich interessieren.

So diene ich bei dieser Anknüpfung von Beziehungen auch als Schriftsteller, Schulmeister und Journalist. Ungern belehre und erkläre ich, lieber erfahre ich etwas;”

Einen wie Masaryk könnte Europa wahrhaft brauchen.

— Schlesinger

PS.: Einen herzlichen Willkommensgruss für Obama mit Rückblick auf Masaryk kann man auf diesem tschechischen Blog finden.

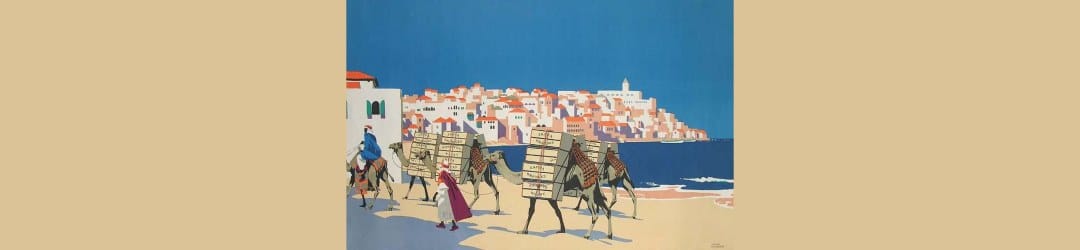

(Text & Bild-Quelle: Karel Capek: “Gespräche mit Masaryk”

Verlagsgesellschaft Sachon)

Die Rede Barack Obamas in Prag finden Sie im Folgenden:

REMARKS BY PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA

Hradcany Square

Prague, Czech Republic

10:21 A.M. (Local)

PRESIDENT OBAMA: Thank you so much. Thank you for this wonderful welcome. Thank you to the people of Prague. Thank you to the people of the Czech Republic. (Applause.) Today, I’m proud to stand here with you in the middle of this great city, in the center of Europe. (Applause.) And, to paraphrase one of my predecessors, I am also proud to be the man who brought Michelle Obama to Prague. (Applause.)

To Mr. President, Mr. Prime Minister, to all the dignitaries who are here, thank you for your extraordinary hospitality. And to the people of the Czech Republic, thank you for your friendship to the United States. (Applause.)

I’ve learned over many years to appreciate the good company and the good humor of the Czech people in my hometown of Chicago. (Applause.) Behind me is a statue of a hero of the Czech people –- Tomas Masaryk. (Applause.) In 1918, after America had pledged its support for Czech independence, Masaryk spoke to a crowd in Chicago that was estimated to be over 100,000. I don’t think I can match his record — (laughter) — but I am honored to follow his footsteps from Chicago to Prague. (Applause.)

For over a thousand years, Prague has set itself apart from any other city in any other place. You’ve known war and peace. You’ve seen empires rise and fall. You’ve led revolutions in the arts and science, in politics and in poetry. Through it all, the people of Prague have insisted on pursuing their own path, and defining their own destiny. And this city –- this Golden City which is both ancient and youthful -– stands as a living monument to your unconquerable spirit.

When I was born, the world was divided, and our nations were faced with very different circumstances. Few people would have predicted that someone like me would one day become the President of the United States. (Applause.) Few people would have predicted that an American President would one day be permitted to speak to an audience like this in Prague. (Applause.) Few would have imagined that the Czech Republic would become a free nation, a member of NATO, a leader of a united Europe. Those ideas would have been dismissed as dreams.

We are here today because enough people ignored the voices who told them that the world could not change.

We’re here today because of the courage of those who stood up and took risks to say that freedom is a right for all people, no matter what side of a wall they live on, and no matter what they look like.

We are here today because of the Prague Spring –- because the simple and principled pursuit of liberty and opportunity shamed those who relied on the power of tanks and arms to put down the will of a people.

We are here today because 20 years ago, the people of this city took to the streets to claim the promise of a new day, and the fundamental human rights that had been denied them for far too long. Sametová Revoluce — (applause) — the Velvet Revolution taught us many things. It showed us that peaceful protest could shake the foundations of an empire, and expose the emptiness of an ideology. It showed us that small countries can play a pivotal role in world events, and that young people can lead the way in overcoming old conflicts. (Applause.) And it proved that moral leadership is more powerful than any weapon.

That’s why I’m speaking to you in the center of a Europe that is peaceful, united and free -– because ordinary people believed that divisions could be bridged, even when their leaders did not. They believed that walls could come down; that peace could prevail.

We are here today because Americans and Czechs believed against all odds that today could be possible. (Applause.)

Now, we share this common history. But now this generation -– our generation -– cannot stand still. We, too, have a choice to make. As the world has become less divided, it has become more interconnected. And we’ve seen events move faster than our ability to control them -– a global economy in crisis, a changing climate, the persistent dangers of old conflicts, new threats and the spread of catastrophic weapons.

None of these challenges can be solved quickly or easily. But all of them demand that we listen to one another and work together; that we focus on our common interests, not on occasional differences; and that we reaffirm our shared values, which are stronger than any force that could drive us apart. That is the work that we must carry on. That is the work that I have come to Europe to begin. (Applause.)

To renew our prosperity, we need action coordinated across borders. That means investments to create new jobs. That means resisting the walls of protectionism that stand in the way of growth. That means a change in our financial system, with new rules to prevent abuse and future crisis. (Applause.)

And we have an obligation to our common prosperity and our common humanity to extend a hand to those emerging markets and impoverished people who are suffering the most, even though they may have had very little to do with financial crises, which is why we set aside over a trillion dollars for the International Monetary Fund earlier this week, to make sure that everybody — everybody — receives some assistance. (Applause.)

Now, to protect our planet, now is the time to change the way that we use energy. (Applause.) Together, we must confront climate change by ending the world’s dependence on fossil fuels, by tapping the power of new sources of energy like the wind and sun, and calling upon all nations to do their part. And I pledge to you that in this global effort, the United States is now ready to lead. (Applause.)

To provide for our common security, we must strengthen our alliance. NATO was founded 60 years ago, after Communism took over Czechoslovakia. That was when the free world learned too late that it could not afford division. So we came together to forge the strongest alliance that the world has ever known. And we should — stood shoulder to shoulder — year after year, decade after decade –- until an Iron Curtain was lifted, and freedom spread like flowing water.

This marks the 10th year of NATO membership for the Czech Republic. And I know that many times in the 20th century, decisions were made without you at the table. Great powers let you down, or determined your destiny without your voice being heard. I am here to say that the United States will never turn its back on the people of this nation. (Applause.) We are bound by shared values, shared history — (applause.) We are bound by shared values and shared history and the enduring promise of our alliance. NATO’s Article V states it clearly: An attack on one is an attack on all. That is a promise for our time, and for all time.

The people of the Czech Republic kept that promise after America was attacked; thousands were killed on our soil, and NATO responded. NATO’s mission in Afghanistan is fundamental to the safety of people on both sides of the Atlantic. We are targeting the same al Qaeda terrorists who have struck from New York to London, and helping the Afghan people take responsibility for their future. We are demonstrating that free nations can make common cause on behalf of our common security. And I want you to know that we honor the sacrifices of the Czech people in this endeavor, and mourn the loss of those you’ve lost.

But no alliance can afford to stand still. We must work together as NATO members so that we have contingency plans in place to deal with new threats, wherever they may come from. We must strengthen our cooperation with one another, and with other nations and institutions around the world, to confront dangers that recognize no borders. And we must pursue constructive relations with Russia on issues of common concern.

Now, one of those issues that I’ll focus on today is fundamental to the security of our nations and to the peace of the world -– that’s the future of nuclear weapons in the 21st century.

The existence of thousands of nuclear weapons is the most dangerous legacy of the Cold War. No nuclear war was fought between the United States and the Soviet Union, but generations lived with the knowledge that their world could be erased in a single flash of light. Cities like Prague that existed for centuries, that embodied the beauty and the talent of so much of humanity, would have ceased to exist.

Today, the Cold War has disappeared but thousands of those weapons have not. In a strange turn of history, the threat of global nuclear war has gone down, but the risk of a nuclear attack has gone up. More nations have acquired these weapons. Testing has continued. Black market trade in nuclear secrets and nuclear materials abound. The technology to build a bomb has spread. Terrorists are determined to buy, build or steal one. Our efforts to contain these dangers are centered on a global non-proliferation regime, but as more people and nations break the rules, we could reach the point where the center cannot hold.

Now, understand, this matters to people everywhere. One nuclear weapon exploded in one city -– be it New York or Moscow, Islamabad or Mumbai, Tokyo or Tel Aviv, Paris or Prague –- could kill hundreds of thousands of people. And no matter where it happens, there is no end to what the consequences might be -– for our global safety, our security, our society, our economy, to our ultimate survival.

Some argue that the spread of these weapons cannot be stopped, cannot be checked -– that we are destined to live in a world where more nations and more people possess the ultimate tools of destruction. Such fatalism is a deadly adversary, for if we believe that the spread of nuclear weapons is inevitable, then in some way we are admitting to ourselves that the use of nuclear weapons is inevitable.

Just as we stood for freedom in the 20th century, we must stand together for the right of people everywhere to live free from fear in the 21st century. (Applause.) And as nuclear power –- as a nuclear power, as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act. We cannot succeed in this endeavor alone, but we can lead it, we can start it.

So today, I state clearly and with conviction America’s commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons. (Applause.) I’m not naive. This goal will not be reached quickly –- perhaps not in my lifetime. It will take patience and persistence. But now we, too, must ignore the voices who tell us that the world cannot change. We have to insist, “Yes, we can.” (Applause.)

Now, let me describe to you the trajectory we need to be on. First, the United States will take concrete steps towards a world without nuclear weapons. To put an end to Cold War thinking, we will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same. Make no mistake: As long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies –- including the Czech Republic. But we will begin the work of reducing our arsenal.

To reduce our warheads and stockpiles, we will negotiate a new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty with the Russians this year. (Applause.) President Medvedev and I began this process in London, and will seek a new agreement by the end of this year that is legally binding and sufficiently bold. And this will set the stage for further cuts, and we will seek to include all nuclear weapons states in this endeavor.

To achieve a global ban on nuclear testing, my administration will immediately and aggressively pursue U.S. ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. (Applause.) After more than five decades of talks, it is time for the testing of nuclear weapons to finally be banned.

And to cut off the building blocks needed for a bomb, the United States will seek a new treaty that verifiably ends the production of fissile materials intended for use in state nuclear weapons. If we are serious about stopping the spread of these weapons, then we should put an end to the dedicated production of weapons-grade materials that create them. That’s the first step.

Second, together we will strengthen the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a basis for cooperation.

The basic bargain is sound: Countries with nuclear weapons will move towards disarmament, countries without nuclear weapons will not acquire them, and all countries can access peaceful nuclear energy. To strengthen the treaty, we should embrace several principles. We need more resources and authority to strengthen international inspections. We need real and immediate consequences for countries caught breaking the rules or trying to leave the treaty without cause.

And we should build a new framework for civil nuclear cooperation, including an international fuel bank, so that countries can access peaceful power without increasing the risks of proliferation. That must be the right of every nation that renounces nuclear weapons, especially developing countries embarking on peaceful programs. And no approach will succeed if it’s based on the denial of rights to nations that play by the rules. We must harness the power of nuclear energy on behalf of our efforts to combat climate change, and to advance peace opportunity for all people.

But we go forward with no illusions. Some countries will break the rules. That’s why we need a structure in place that ensures when any nation does, they will face consequences.

Just this morning, we were reminded again of why we need a new and more rigorous approach to address this threat. North Korea broke the rules once again by testing a rocket that could be used for long range missiles. This provocation underscores the need for action –- not just this afternoon at the U.N. Security Council, but in our determination to prevent the spread of these weapons.

Rules must be binding. Violations must be punished. Words must mean something. The world must stand together to prevent the spread of these weapons. Now is the time for a strong international response — (applause) — now is the time for a strong international response, and North Korea must know that the path to security and respect will never come through threats and illegal weapons. All nations must come together to build a stronger, global regime. And that’s why we must stand shoulder to shoulder to pressure the North Koreans to change course.

Iran has yet to build a nuclear weapon. My administration will seek engagement with Iran based on mutual interests and mutual respect. We believe in dialogue. (Applause.) But in that dialogue we will present a clear choice. We want Iran to take its rightful place in the community of nations, politically and economically. We will support Iran’s right to peaceful nuclear energy with rigorous inspections. That’s a path that the Islamic Republic can take. Or the government can choose increased isolation, international pressure, and a potential nuclear arms race in the region that will increase insecurity for all.

So let me be clear: Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile activity poses a real threat, not just to the United States, but to Iran’s neighbors and our allies. The Czech Republic and Poland have been courageous in agreeing to host a defense against these missiles. As long as the threat from Iran persists, we will go forward with a missile defense system that is cost-effective and proven. (Applause.) If the Iranian threat is eliminated, we will have a stronger basis for security, and the driving force for missile defense construction in Europe will be removed. (Applause.)

So, finally, we must ensure that terrorists never acquire a nuclear weapon. This is the most immediate and extreme threat to global security. One terrorist with one nuclear weapon could unleash massive destruction. Al Qaeda has said it seeks a bomb and that it would have no problem with using it. And we know that there is unsecured nuclear material across the globe. To protect our people, we must act with a sense of purpose without delay.

So today I am announcing a new international effort to secure all vulnerable nuclear material around the world within four years. We will set new standards, expand our cooperation with Russia, pursue new partnerships to lock down these sensitive materials.

We must also build on our efforts to break up black markets, detect and intercept materials in transit, and use financial tools to disrupt this dangerous trade. Because this threat will be lasting, we should come together to turn efforts such as the Proliferation Security Initiative and the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism into durable international institutions. And we should start by having a Global Summit on Nuclear Security that the United States will host within the next year. (Applause.)

Now, I know that there are some who will question whether we can act on such a broad agenda. There are those who doubt whether true international cooperation is possible, given inevitable differences among nations. And there are those who hear talk of a world without nuclear weapons and doubt whether it’s worth setting a goal that seems impossible to achieve.

But make no mistake: We know where that road leads. When nations and peoples allow themselves to be defined by their differences, the gulf between them widens. When we fail to pursue peace, then it stays forever beyond our grasp. We know the path when we choose fear over hope. To denounce or shrug off a call for cooperation is an easy but also a cowardly thing to do. That’s how wars begin. That’s where human progress ends.

There is violence and injustice in our world that must be confronted. We must confront it not by splitting apart but by standing together as free nations, as free people. (Applause.) I know that a call to arms can stir the souls of men and women more than a call to lay them down. But that is why the voices for peace and progress must be raised together. (Applause.)

Those are the voices that still echo through the streets of Prague. Those are the ghosts of 1968. Those were the joyful sounds of the Velvet Revolution. Those were the Czechs who helped bring down a nuclear-armed empire without firing a shot.

Human destiny will be what we make of it. And here in Prague, let us honor our past by reaching for a better future. Let us bridge our divisions, build upon our hopes, accept our responsibility to leave this world more prosperous and more peaceful than we found it. (Applause.) Together we can do it.

Thank you very much. Thank you, Prague. (Applause.)